Apart from a few years living in Livingston, Edinburgh has always been home for me. I enjoy discovering the city’s history, seeing how it changes, visiting local pubs, and learning about the stories behind its street names. Like most cities, Edinburgh has streets named after people, places, events, jobs, and how they were used. But some names are less straightforward. Many of my relatives came from Pleasance and Dumbiedykes, and these unusual names made me curious about where some of the city’s more unique names come from.

Pleasance is a road running from Holyrood Road to its junction with St Leonard’s Street. Many call it “The” Pleasance, which irritates locals who insist there is no definite article. Some records suggest there was once a nunnery on this road, beyond the city limits, built in honour of St. Mary of Placentia, the original Latin name of the city of Piacenza in northern Italy. Over time, the street became known for its religious associations, and gradually ‘Placentia’ evolved into ‘’Pleasance’.

Religious scholars note there is no Saint Mary of Placentia, and archaeologists have not identified any historic nunnery or church building in this area of Edinburgh. A more likely origin is that the land here, beyond the city

walls, served as a pleasant place where residents could stretch their legs, breathe fresh air, and briefly escape the unsanitary city.

Many of my relations lived on street off Pleasance and others were member of the “Pleasance Trust Mixed Group”.

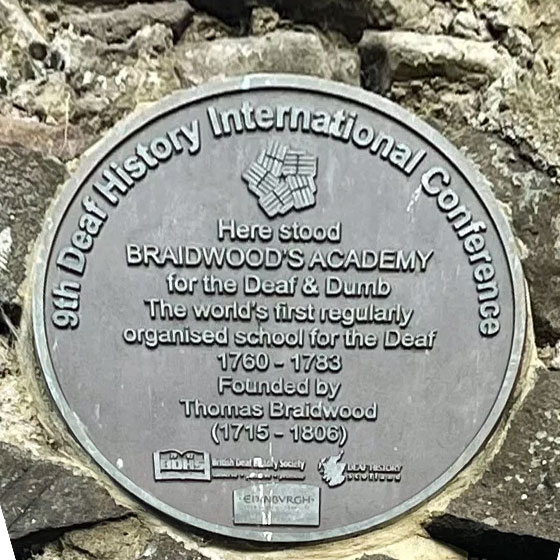

Many of my relatives lived at 160 Dumbiedykes Road. The name comes from a derogatory nickname for pupils at Thomas Braidwood’s Academy for Deaf and Dumb Children, which used to be nearby, and from the Scots word “dyke,” meaning a wall or boundary.

Edinburgh has a long list of firsts. It was the site of the world’s first general medical practice and the first municipal fire service. The city also had the world’s first deaf school. Braidwood’s Academy for the Deaf and Dumb opened in 1760 with just one pupil. Thanks to the teacher’s success, the school soon grew to 20 children. Today, all that remains is a plaque on the stone wall.

The school did very well in its early years. Braidwood’s teaching style focused on natural gestures instead of the spoken methods used in other parts of Europe, which made his approach popular. When the school moved to Hackney in London, the building was demolished in 1883, but the walls were left standing.

Back in the late 18th century, it was not uncommon for people to refer to those suffering serious speech impairment as ”dumbies’

Referring to those unable to speak, the word ‘dumb’ is now outdated and considered highly offensive, but, in the 1760s, it was still being used as official terminology.

South of the city centre is Sciennes (pronounced ‘sheens’), which derives from a Dominican convent that once stood in the area. It was dedicated to St Catherine of Scienna, itself a French spelling of the name of the town in Italy (Sienna) where she had lived.

Built around 1518, St Catherine’s Convent was destroyed only half a century or so later, in 1567, around the time of the Reformation in Scotland.

Its stones, and those of the high walls which surrounded the site, were gradually taken and incorporated into other buildings, meaning no physical evidence of the convent survives today — except for a memorial marker on one of the original stones of the building in the front garden of a property on St Catherine’s Place, and the name which it gave to the surrounding streets.

The South Side of Edinburgh, just east of Salisbury Crags, was where many of my Barclay and Galloway relatives lived over the centuries, on streets like Salisbury Street, Carnegie Street, and Pleasance. Close by are Crosscauseway

and Causewayside. Their names come from a mistranslation of the French word ‘causey’, meaning a paved street, probably from the French ‘chaussée’. This word was used for the old paved road that crossed the Burgh Muir and later

became part of the city. The area was once known as ‘The Causey’, and in the 16th century, it was the main route from Edinburgh to Liberton. Even now, locals sometimes call it ‘Causeyside’, which might be a better name.

At the junction of West Crosscauseway and Buccleuch Street is the curiously named “Guse Dub”. Translated from Scots, the name ‘Guse Dub’ means, literally, ‘Goose Puddle’, and the junction historically was the site of a public

wellspring and a small pond where ducks and geese congregated, at a time when this area was rural territory, well beyond the limits of Edinburgh’s city wall.

Not far to the west of Guse Dub, you’ll find Windmill Street, which has an unusual name. While Edinburgh had plenty of water mills, especially by the Water of Leith, windmills were much rarer.

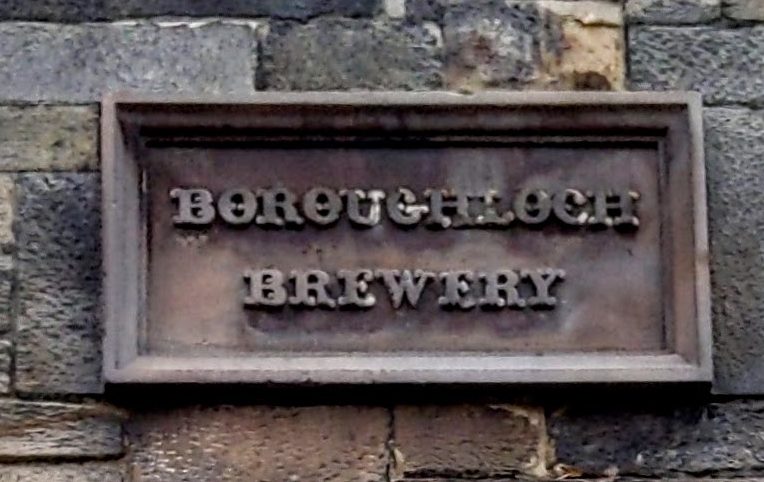

This street was originally located near the South Loch, which was drained in 1722 to make way for the Meadows. The street was named after the windmill that stood nearby and powered pumps to supply water from the Loch to the Society of Brewers’ brewery near what is now Chambers Street. Although Edinburgh was surrounded by boggy, poorly drained land, finding clean water was always a challenge. Many breweries had their own wells to ensure water quality and often had to drill as deep as 180 metres. The South Loch was also called the Boroughloch. The name of the Boroughloch Brewery, which closed in the early 1900s, can still be seen on an archway at the entrance to the brewery on Boroughloch Street, a short walk south of Windmill Street.

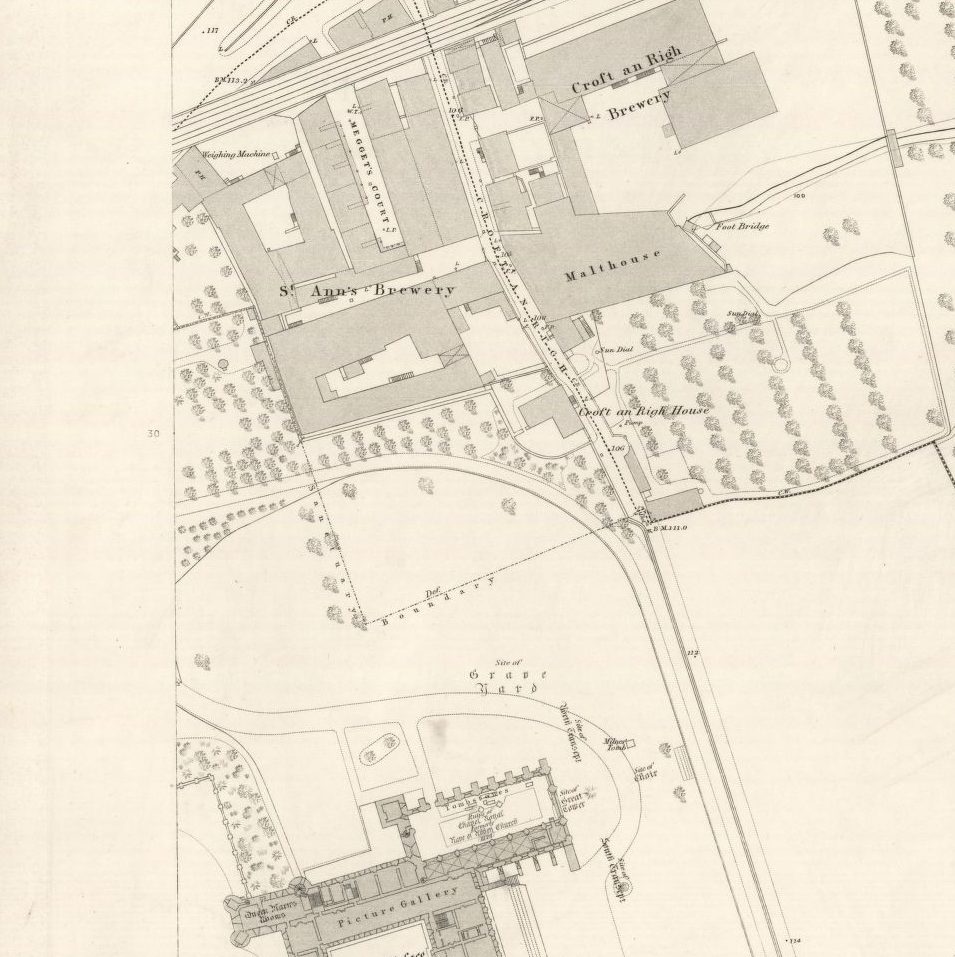

Ten years after her husband’s death, my great-great-great-grandmother Isabella (or Margaret) Galloway was living at Croft an Righ, a small area adjacent to Holyrood Palace, referred to on street signs as Croft-an-Righ. On the face of it, this would seem to simply be a slightly anglicised version of Gaelic Croit an Rìgh, ‘the King’s croft’. This would seem appropriate given the royal location; indeed, it is referred to as such in a nineteenth-century Gaelic book.

The name as it appears now, however, is misleading; in 1781, it is on record as Croft Angry. Several other places with such a name exist in Scotland, including two in Fife. These are Scots names containing croft with an element angry; this is of uncertain meaning as it seems only to have survived in place-names; it is related to German anger ‘(small) meadow’. Possibly it means a ‘fenced grazing in the croft or arable infield’ or perhaps more simply ‘grassland’

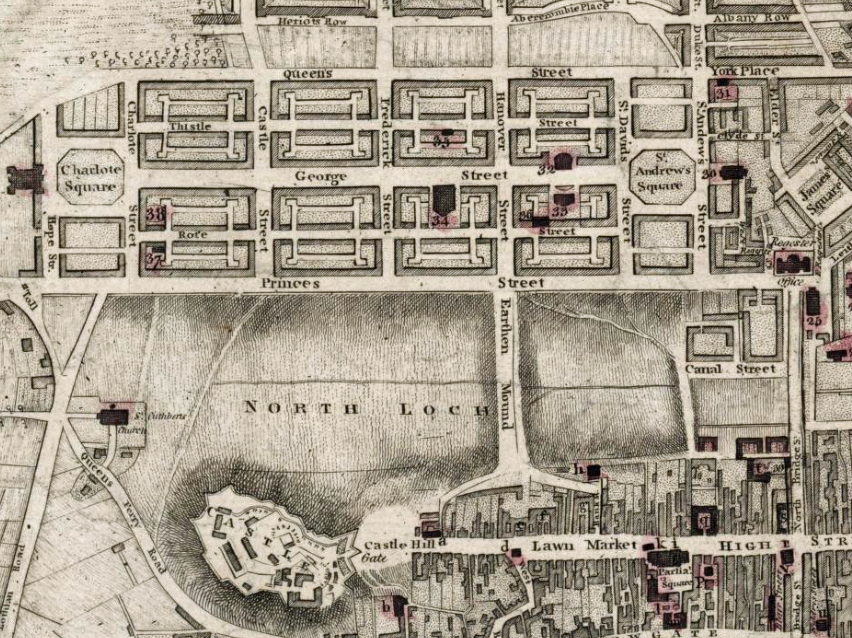

The Mound in Edinburgh gets its name from its history as an artificial hill, created by dumping earth excavated during the construction of the New Town in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The project began as a simple suggestion by a shopkeeper named George Boyd, who proposed a temporary plank bridge across the muddy Nor Loch (North Loch) to create a shortcut between the Old Town and the New Town. It was first known as “Geordie Boyd’s Brig” and later as “the Earthen Mound”. Over the course of about 50 years, millions of cartloads of earth and debris from the New Town construction were dumped into the loch, eventually forming a massive, permanent causeway. The loch was finally drained in 1817. The Mound was macadamized and landscaped in the 1830s, assuming its current shape

The National Library of Scotland offers a great map reading room, and much of it is free online. I often use this resource to add a geographical perspective to information. Old maps can also show schools, churches, factories, and other places of employment.

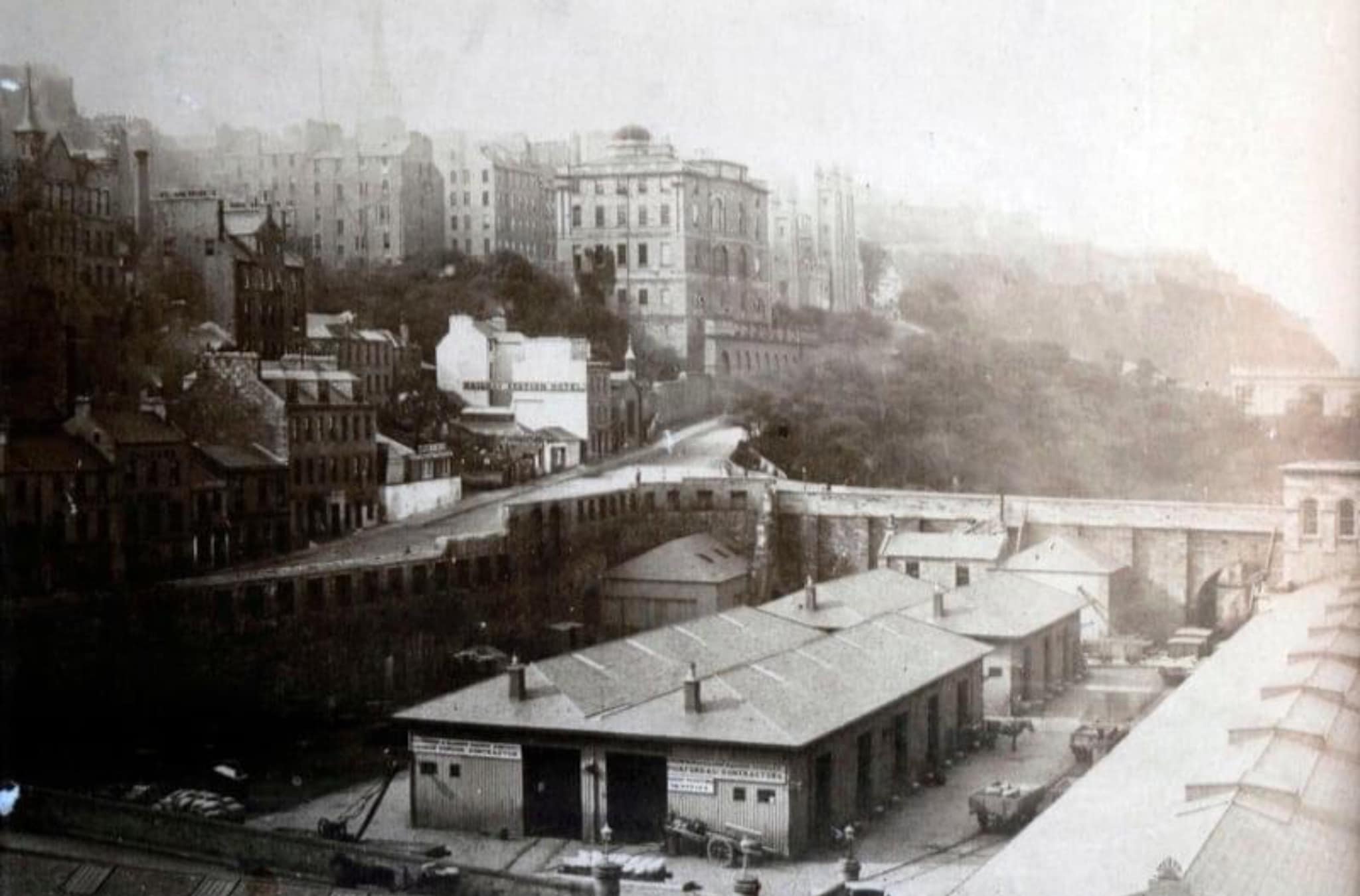

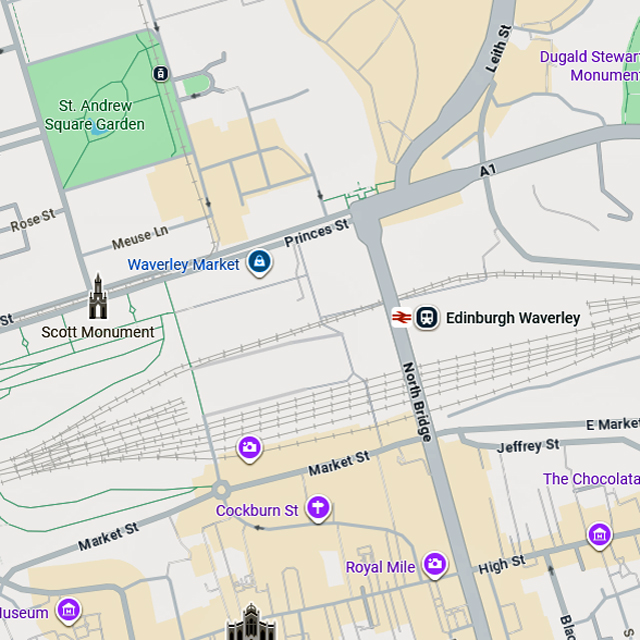

I live close to the Union Canal, which runs from Edinburgh to Falkirk. During my research, I discovered that one of my great-great-grandfathers lived on Canal Street. I didn’t know of any modern street with this name, but old maps showed it was near where Waverley Station now stands. This intrigued me, since there is no canal near the station, so I looked into it further.

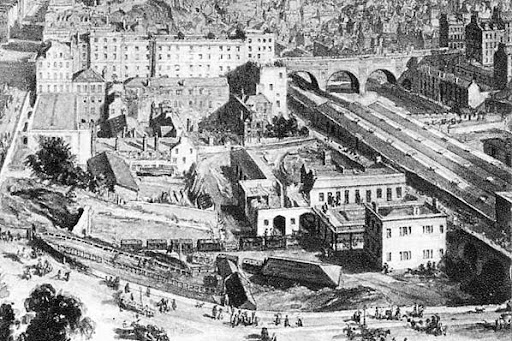

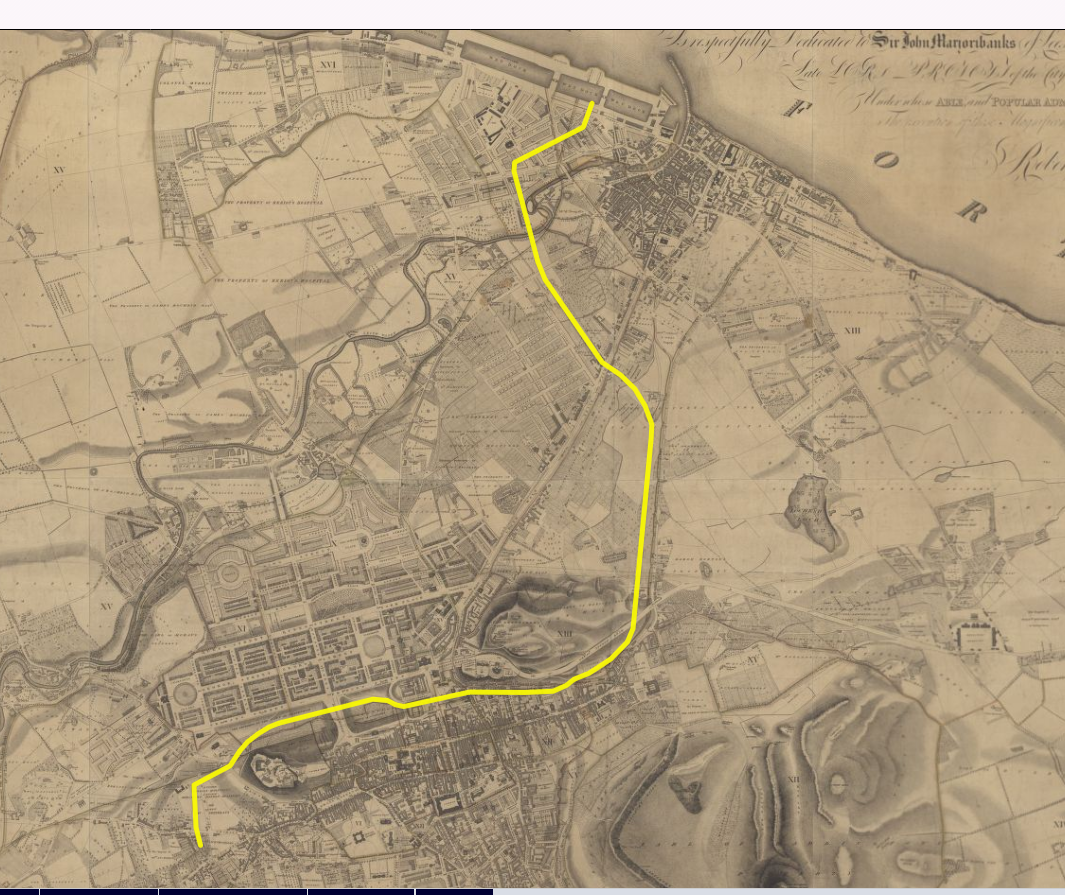

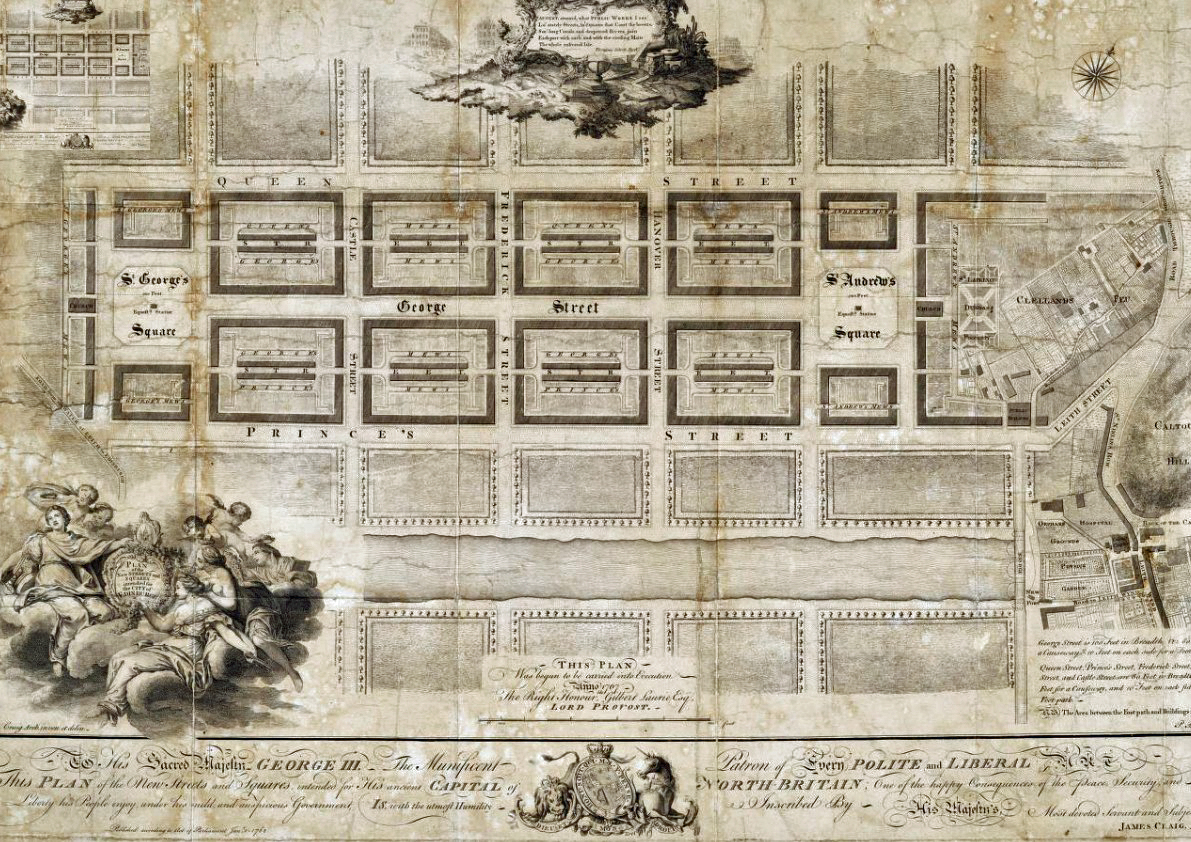

With much of the population crowded around the Castle, Edinburgh was in the doldrums. An air of lethargy hung over the city, which had about 25,000 people in 1700. Old houses were decaying, and some collapsed. The streets and closes were dirty and needed repair, and disease was rife. The first half of the century is often called the Dark Age of Edinburgh. In 1766, a design competition was held to create a new urban area to ease the severe overcrowding, squalor, and disease in the Old Town. The competition was won by James Craig, a relatively unknown 26-year-old architect. He proposed a simple, geometric grid of elegant avenues, squares, and gardens. His design included a stretch of canal with promenades and walkways through what is now Princes Street Gardens, on the site of the drained Nor’ Loch. Canal Street was between Waverley Bridge and the North Bridge at the eastern end of the proposed canal. The canal was never built, but Canal Street remained. Studying other maps, I found there were plans to extend the Union Canal from Port Hopetoun in Tollcross, through Princes Street Gardens, and then on to Leith. Again, this was never built, and the canal terminated at Port Hopetoun.

Although there was never a terminus for canal traffic, between 1847 and 1867, a railway line ran from Canal Street Station to connect with the Leith and Newhaven Railway. Today, the site of the terminus is part of Waverley Station, and the original tunnel portal for trains arriving at Canal Street can still be seen at the northern end of Waverley Station Platform 19.