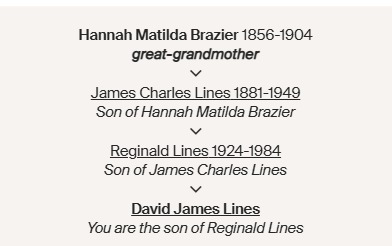

Hannah Matilda Brazier, my great-grandmother, was born on 3 February 1856 at 7 Hill Place Street, Poplar.

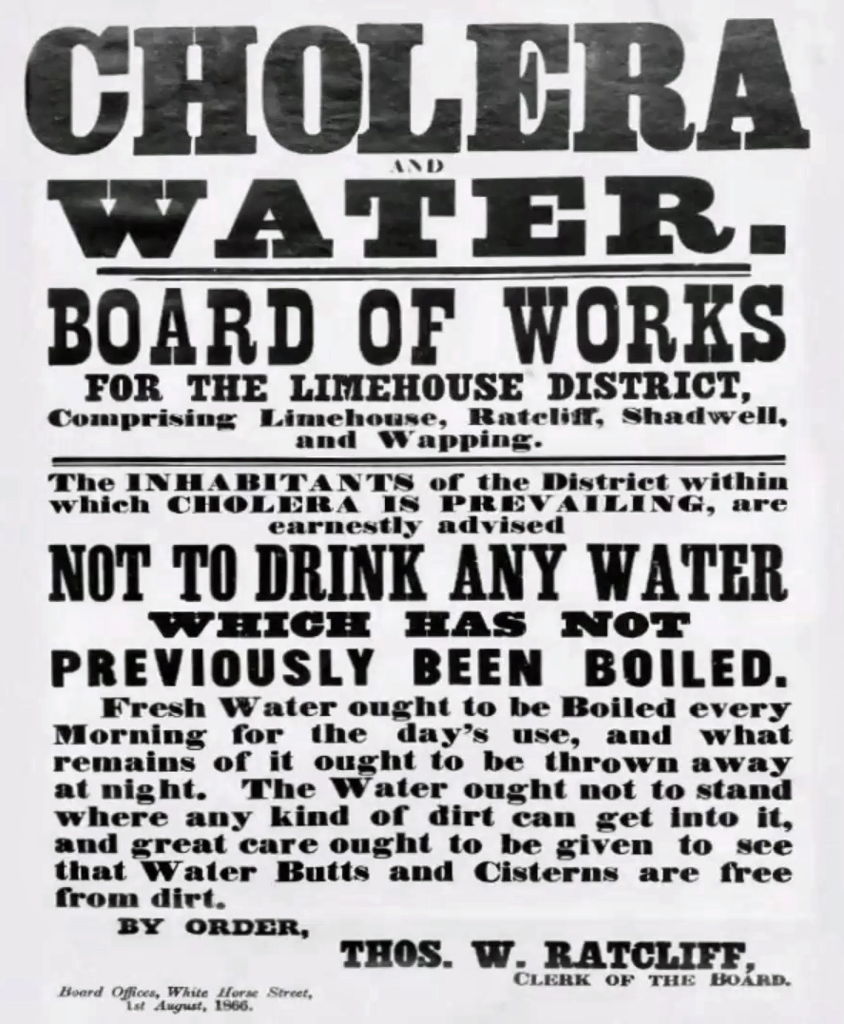

In the 19th century, London’s Poplar area changed from a semi-rural hamlet to a densely populated, poverty-stricken industrial zone dominated by shipping and docks. It became synonymous with poverty and disease, mainly because of poor housing, overcrowding near docks and factories, and low wages. At the north end of Hill Place Street was the Limehouse Cut, a canal built in 1770 as a shortcut between the River Lee and the Thames, lined with factories and slum housing. Throughout the 19th century, London’s poor sewage system meant human and industrial waste were often dumped directly into the city’s waterways. Many poor residents had no access to clean drinking water and had to draw it daily from the canal.

Bow Common Lane Bridge, which crossed Limehouse Cut, was because it was flanked by a rubber and bone works, a felt works, and a tar and resin distillery, was known as “Stinkhouse Bridge”

In 1871, at the age of five, Hannah was living in Tower Hamlets with her parents, William and Jane, her elder sister Martha (16), a factory worker, and her younger sister, Jane. Ten years later, at fifteen, Hannah is living away from home, working as a house and domestic servant at 139 High Street, West Ham.

Life was likely very hard for the family, especially for a young girl working in domestic service, sometimes called a ‘slavey maid.’ These maids, often scullery maids, did the toughest and dirtiest kitchen jobs, like washing dishes and scrubbing floors. The work was exhausting, with long hours, poor living conditions, and very few breaks or comforts. They usually worked under the cook’s watch and were not allowed to eat with the other servants.

Hannah married Frederick Charles Lines in 1876 at St Thomas’s Church, Tower Hamlets. In 1891, the family was living on Church Street, Canning Town, with their children: Frederick (13), William (10), James (9), Charles (7), Elizabeth (5), and Hannah (3). Canning Town was another notoriously disease and poverty-ridden area.

Canning Town was another slum area in London’s East End. It developed from desolate marshland in the mid-19th century into a significant industrial and dock-based settlement before being devastated by World War II bombs. Being outside London’s jurisdiction in Essex, Canning Town attracted “noxious” industries and speculative builders unburdened by strict regulations.

One of the most pressing issues for those living in the Canning Town slums was the lack of adequate housing, unsanitary conditions characterised by overcrowding, poor drainage, open sewers, and frequent flooding. Many families lived in cramped, poorly ventilated tenement buildings with no running water or indoor plumbing. These conditions often led to the spread of disease, with illnesses like cholera, typhoid fever, and tuberculosis particularly prevalent.

Some disaster must have befallen the family, as on 18 February 1893, Hannah and her daughter, Edith (Eliza), were admitted to the Workhouse in Paddington. People ended up in the workhouse for various reasons, usually because they were too poor, old, or ill to support themselves. Workhouses were not prisons, and entry was generally voluntary, though often a painful decision. They were to be transferred from Paddington to the Hendon Union Workhouse in Burnt Oak, but before travelling, Hannah chose to discharge herself and Edith, presumably to return to the family at 75 Percy Road in Canning Town.

Hannah spent her entire life in London’s East End. Her father died in 1892 at Percy Road, and Hannah and her family moved into this home, where she spent her final years and died on 28 September 1904.

It’s hard to imagine how miserable her life might have been. Born into a poor family, moving from one slum area of East London to another, spending her teenage years as a Slavey Maid, forced into a short time in a Workhouse, and dying at the relatively young age of 48.

Comments are closed