Cholera in the 19th century was especially terrible because of its fast, violent symptoms, high death rate, and lack of understanding about its cause. The disease hit the poor in crowded, dirty cities the hardest. People suffered severe stomach cramps, vomiting, and diarrhoea, which quickly led to dehydration. Their eyes would sink, their skin would shrivel and turn blue from lack of oxygen. This is why it was called the “blue death.” Many died within a day of getting sick. The speed and horror of cholera made it the most feared disease of its time.

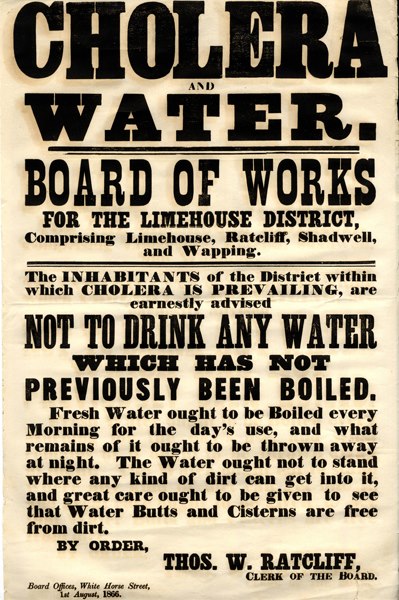

From late June to autumn 1866, a severe cholera outbreak hit London’s East End. This was Britain’s last major urban cholera epidemic and convinced many officials that cholera spread through contaminated water, not “miasma” or “bad air”.

During the 1866 cholera outbreak in London, my great-great-grandfather Frederick Lines, his wife Hannah, and two of their children died.