When I was young, we often went on family holidays to the south of England: Cornwall, Devon, Hayling Island, but most often Southampton. Dad would drive from Edinburgh, the steady hum of the engine and faint smell of petrol marking our journey. I remember peering out the window at the first glimpse of the Solent, its vast expanse of water gleaming in the sun, and the salty breeze promising adventure. We would stay with Dad’s relations in Bishop’s Waltham or Beaulieu. These trips made me think Dad’s family came from Hampshire. However, my ancestry research showed that many of them originated in London’s East End.

My maternal ancestors weren’t affluent; they were mostly manual workers, with the occasional tradesman or shopkeeper. They often moved from the countryside to poorer areas of Edinburgh and endured hard times, but I was surprised by how much more poverty my paternal ancestors faced.

My paternal grandparents, four great-grandparents, and four great-great-grandparents were born and lived in London’s East End, with many others coming from towns and villages just outside London. Places in Essex like Romford, Doddinghurst, Ilford, Dagenham, Barking, and Billericay were drawn to London for employment.

Frederick Lines, my great-great-grandfather, was born in Barking in March 1827. In the early 19th century, Barking was a significant fishing port that shifted to market gardening and later to industrial development, marked by the arrival of the railway in 1854. The 1866 Cholera Outbreak in London claimed thousands of lives, including Frederick, his wife, and two of his children. Two children were taken into care; it’s uncertain what happened to the other two, James and Frederick Charles Lines, my great-grandfather.

I wanted to learn more about the lives my East End ancestors might have led.

Cholera and smallpox were constant threats in 19th-century London. My paternal great-grandmother, Hannah Matilda Brazier, was born on Hill Place Street, Poplar, on 3 February 1856. In the early 19th century, much of Poplar, around the Limehouse Cut, was open countryside. Before she married Frederick Charles Lines in 1876, she lived with her family on South Hill Street, which ran south from the Limehouse Cut Canal.

The map on the left shows the docks at the Isle of Dogs and the Limehouse Cut, a canal linking the River Lea to the River Thames and is surrounded by open land. In the mid to late 1800s, Poplar’s population grew quickly, and the map on the right shows the crowded housing and factories from that time.

At the north end of Hill Place Street was the Limehouse Cut. Built in 1770, it was London’s first canal, connecting the River Thames to the River Lea. The canal gave barges a direct, tide-free route to carry goods like coal, pig iron, and salt, so they didn’t have to take the long way around the Isle of Dogs or deal with the Thames tides. In the early 1800s, factories and workshops sprang up along the canal, including lime kilns (which gave the area its name), sawmills, soap makers, potash works, cable makers, gasworks, and chemical factories that made tar, varnish, ammonia, and more.

Near the River Lea end of the canal is Stinkhouse Bridge, also known as Stink Bridge. The name came from the bad smells from nearby factories, like rubber works, bone works, felt works, and a tar-and-resin distillery. Poor sanitation and factory waste dumped into the canal made the area smell even worse. The map above shows a common sewer running from the bridge, the infamous “Black Ditch”. Many people living nearby got their water from the canal because they didn’t have running water at home, so they used it for drinking, cooking, and cleaning.

These unsanitary conditions led to disease, and in 1832, as the first case of cholera appeared in the country at Limehouse, panic quickly spread, and over 800 deaths were recorded along East London’s riverfront during that epidemic—Limehouse being a main hotspot. Reports in 1849 described the Limehouse Cut as “a receptacle for dead dogs, cats, and other small animals, frequently seen floating on the discoloured waters” and noted that cholera deaths occurred among people who drank the water from the canal.

Limehouse wasn’t the only area of 19th-century London with open sewers. The rapid industrial and residential growth in areas like West Ham and Hackney outpaced infrastructure. Human waste and industrial effluent were routinely discharged into local streams and ditches. The “Little Tommy Lea” sewer was an open sewer located in Canning Town, London, specifically running behind Pretoria Road.

At 15, Hannah was a maid servant for a family in West Ham. Domestic service in London’s East End during the late 19th century was a massive employer. So-called “slavey maids” were pauper girls, frequently discharged from workhouses, or came from poor families. Without support or prospects, many entered domestic service as their only means of survival. They were often scullery maids who did the most challenging, dirtiest kitchen work, such as washing dishes and scrubbing floors.

Many of my paternal ancestors in the 19th century were manual workers, whether agricultural workers before moving to London, labourers on the docks and canals, or domestic service like Hannah.

Agricultural labourers faced low wages, poor living conditions, and limited education, resulting in hardship. Labour was physically demanding, and the whole family, including women and children, joined in seasonal tasks like tying straw bands for sheaves.

Moving to London’s East End and being near the River Thames and the London Docks meant that dock labour was a major source of employment, especially in riverside areas like Limehouse and Poplar. This work was often casual, with men gathering daily in hopes of being selected for a day’s wage. General labourers were also employed in railway construction, building houses, and other demanding physical tasks.

In the early 19th century, as London grew and pressure on house-room increased, any open space – remnants of market gardens, marshy meadows not previously profitable for building, or the grounds of former farmhouses – became valuable terrain for the jerry-builder. These fag-end parcels of London clay would be leased for 21 years or even less, so builders had every incentive to put up hovels that would last no longer than that: without foundations; with dirt floors; with walls just half a brick thick; with yards and streets unpaved and without drains.

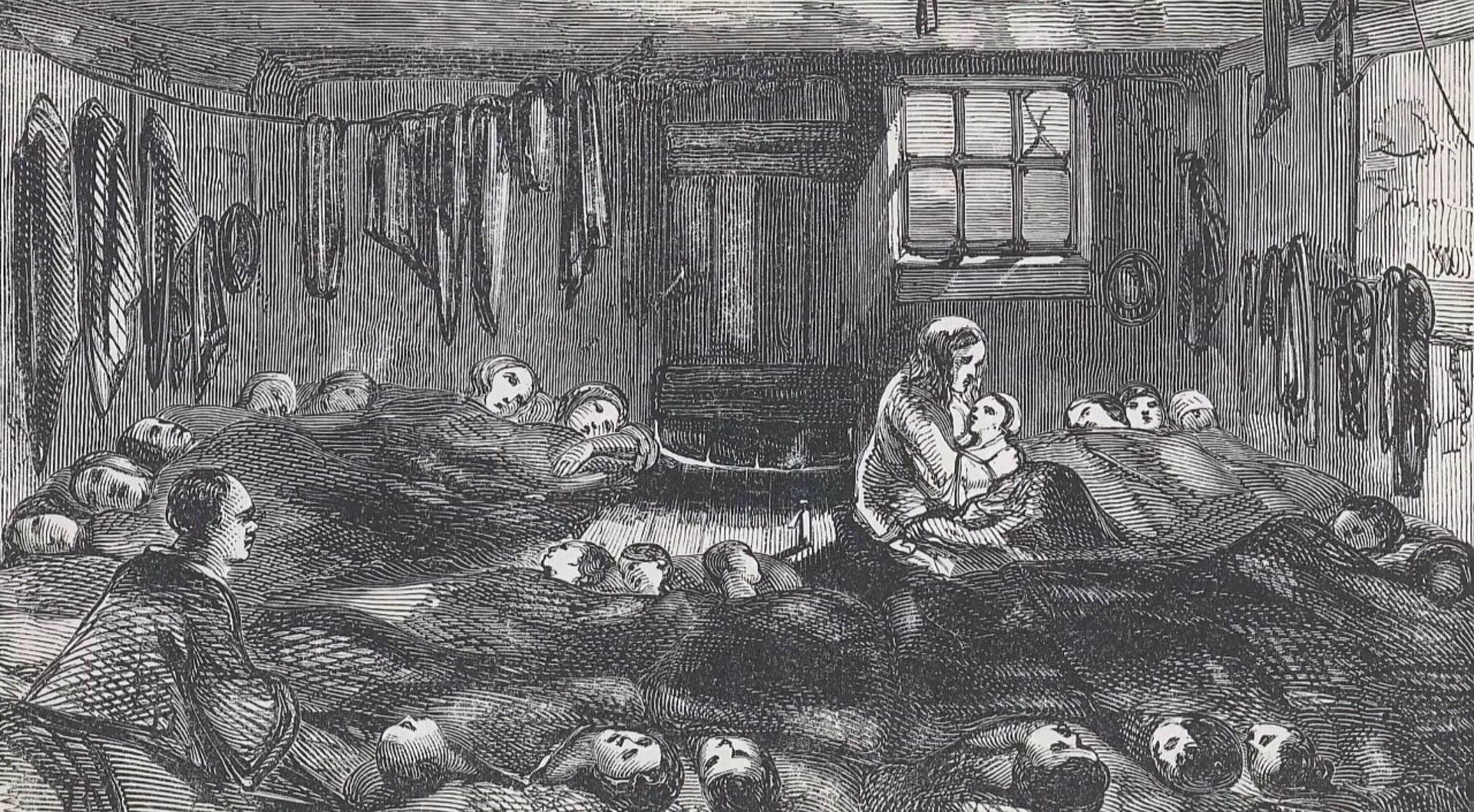

By the mid-1800s, housing in London’s East End, areas like Poplar, Canning Town, and Bow was marked by extreme overcrowding, poor sanitation, and dire poverty. Many families lived together in small terraced houses, sometimes sharing just one room. These homes often lacked ventilation and running water, making it easy for diseases to spread.

People who were too poor, old, or sick to care for themselves often ended up in a workhouse. These institutions in 19th-century London were intended to provide shelter and employment to those in need, but the conditions were deliberately harsh, designed to discourage anyone but the truly desperate from seeking help. When people entered, families were usually separated, with children being taken from their parents and men from their wives, each being sent to different wards. Inmates had to wear uniforms, had very little freedom, and in many workhouses, talking was not allowed.

On 18 February 1893, Hannah and her daughter, Edith (Eliza), were admitted to the Workhouse in Paddington.

The 19th-century East End was a place of extreme overcrowding, filth, frequent death from disease, high infant mortality, grinding poverty, and a relentless struggle for survival.